“If I didn't define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people's fantasies for me and eaten alive.”—Audre Lorde

One might assume that the power of the artist lies in his ability to create his subjects. The series of portraits shown in Barkley L. Hendricks’Heart Hands Eyes Mind, however, finds its unique authority in the artist’s capacity to allow his characters to define themselves. Rather than dictating the terms of their appearances, Hendricks seems to paint his subjects as they themselves would elect to be seen. The result is exhilarating; there is something fundamentally liberating in the decision to give over such a significant measure of control.

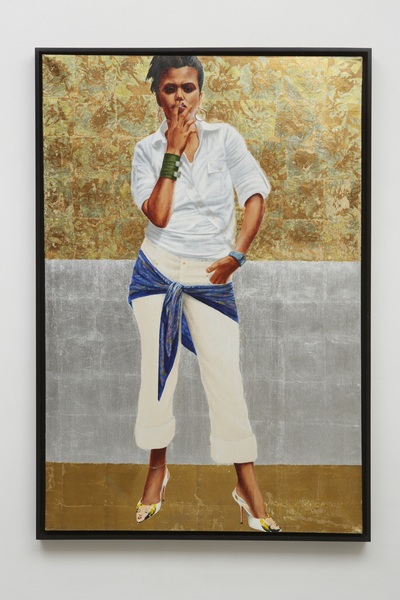

Upon first glance at the paintings on the walls, the majority of which are dated ’11 - ’13, I was unable to discern a connection between the people represented in this new body of work and those of earlier paintings, with whom I am familiar. Where is the self-assured queen depicted in Hendricks’ iconic portrait, Lawdy Mama (1969)?[1] What does the bold, Afro-rocking woman painted during the height of the Black Panther movement have in common with Hendricks’ newer, contemporary black woman who wears blue contact lenses and a bedazzled "SYREETA" name plate belt casually dangled across her nude waist? What do these women share with me? As I stared deep into the unabashedly deceptive eyes of Sweet Señorita Syreeta (2012), it dawned on me: the dominant thread that ties together Hendricks’ subjects is the power of self-expression. If we examine each portrait as a mere fantasy of the artist’s mind, no connection will be made. It is only when we understand that Hendricks grants his subjects the freedom to “speak” for themselves that we locate continuity in his work – that is, the self-possessed, internal gaze of his subjects, who candidly present themselves as they are.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Triple Portrait: World Conqueror, 2011, Oil, aluminum leaf, variegation leaf, and combination gold leaf on linen canvas, 60 x 40 inches; Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

This is the artist’s first solo show with Jack Shainman Gallery and he’s been granted both the 20th Street location (which they have inhabited for sixteen years) and the gallery’s brand new space on West 24th, which opened just this month. In addition to paintings, Hendricks is showing photographs. A series that hangs in a small room of the 24th St. space makes an interesting commentary on race and identity politics. The arrangement begins with a photograph portraying the word "Pure." Next, the artist presents amateur street art depicting boxing legend, Jack Johnson, along with the caption, "Black Jockeys Won the Kentucky." This photograph is then, quite unexpectedly, juxtaposed against a picture depicting a white Jesus, and yet another that contains an image of Marilyn Monroe. Finally, the last photo in the series reads, simply, "FIN." The varying media of the exhibition begin to cohere thematically when we return from these photographs to the first portrait one encounters upon entering the gallery, Triple Portrait: World Conqueror (2011). Here, a racially ambiguous woman takes a drag of her cigarette, one hand slipped confidently into her hip pocket, while sporting high-heeled shoes with the image of Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe painted on the toes. Again, Hendricks reminds us that there is no singular or correct expression of a black identity. How we each choose to define ourselves is a personalization of the seemingly forced dichotomy of races, and the artist permits his subjects to assert blackness in individualized ways.

Through the element of surprise in the organization of Hendricks’ photographs, combined with his objectively painted portraiture, the artist forces his viewers to interrogate the black and white binary into which race is socially constructed. The imposed limits of race run deeper than the surface of the skin, his subjects suggest, and can, therefore, be challenged. In the most subtle, yet subversive ways, Hendricks’ subjects defy the narrow constraints of racial dichotomies, blur the boundaries, and define racial identities independently – on their own terms.

[1]Barkley L. Hendricks, Lawdy Mama, 1969. Oil and gold leaf on canvas, 53 ¾ x 36 ¼ in. Collection of the Studio Museum in Harlem.

(Image on top: Barkley L. Hendricks, Sweet Señorita Syreeta, 2012, Oil and acrylic on linen canvas, 48 x 30 inches; Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)