The spaces of Kaufmann Repetto gallery in Milan smell of blood, medicine and hospital. The walls are covered with a black shiny varnish and the neon lights on the ceiling spread their cold beams over the mirroring tables. The setting looks like a security room or a refrigerating cell – there’s no life here, no wishes, no hopes. Every hint of humanity is properly frozen in the material traces of someone’s passage – a stool slightly moved by an invisible hand, some pale wooden apples scattered around by imaginary guests. An aseptic order dominates the space: the minimal and polished furniture is set up to create a balanced, controlled symmetry.

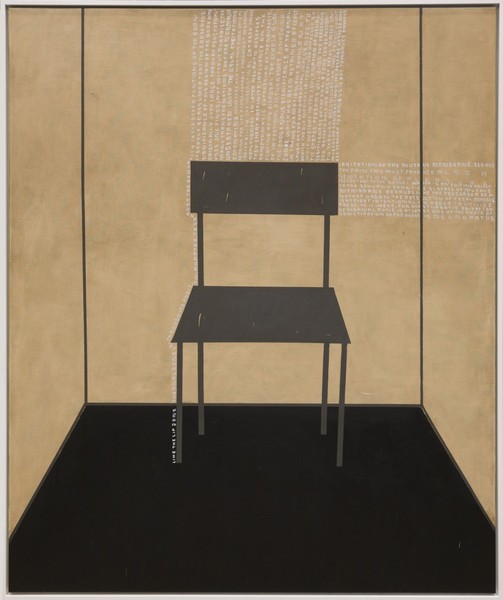

The German artist Thomas Zipp (born in Heppenheim, 1966) is the author of this gloomy and striking installation, titled The Pink Noise Diaries. The pink noise is a particular kind of acoustic signal characterized by more intense low-frequencies: it sounds like a continuous electric interference, an annoying background racket which interrupts the course of our rational thinking. And this is what we can feel passing through the gallery space: the oppressing sensation of an imminent brake, a hardly identifiable disturbance that threatens the artificial order of the objects. The mirror surfaces of the tables are maybe a Lacanian allusion: they reflect our divided Self, ceaselessly vexed by the pink noise of the unconscious. Large oil paintings are hung on the dark walls. Their palette is composed of gray, ochre and brown tones; their forms recall Modernism. Hand-written words and block letters spit out by a crazed typewriter – barely decipherable – occupy most of the painted surface: they are all excerpts from psychoanalytic essays (a vortex of words like ‘libido’, ‘sexuality’, ‘impulse’, ‘paranoia’ invade our mind: now the rooms appear to us as the compartments of a psychiatric clinic).

Thomas Zipp, A. B.: Membranes, 2013, oil and marker on canvas,185 x 155 cm; Courtesy of the artist and Kaufmann Repetto Gallery.

Transforming exhibition venues in their entirety is one of Thomas Zipp’s trademarks: in 2010 he turned the whole space of Kunsthalle Fridericianum in Kassel into a huge psychiatric hospital; more recently he covered the walls of Harris Lieberman Gallery in New York with silver foil, transforming the space into a sort of clinical laboratory. The German artist’s interventions aim at creating a schizophrenic and parallel universe where men are driven by irrational forces, madness and the unconscious – an element, the last one, which ideally connects his practice to Surrealism. His work reveals the importance of the dark, of the grey areas of knowledge; the role of art is disclosing unexpected life perspectives, brushing history against the grain. No surprise that the maudit Zipp once compared painting to taking drugs – they both 'suck you in and open you up to new points'.

The apple is a recurring object in Zipp’s installations. It is a symbol for Western culture: Adam and Eve, the strong temptation of sin, Newton and scientific progress – a form (that of the apple) which represents humanity, our credo and beliefs. But the apples we can see in the Milanese gallery are pale, flimsy and empty; again, Zipp makes uncomfortable what previously could reassure us. His approach is revisionist– he reinterprets history, unmasks the accepted models of science and religion, demolishes the idealistic vision of human progress. Many of Zipp’s past works are portraits of men who gave history a turning point, like Otto Hahn, the father of nuclear chemistry (and of the 'Atomic Era'). The artist – driven by iconoclast fury and new-Dada irreverence – plunges tacks in their eyes, disfiguring their faces with black scribbles; there’s no Enlightenment, no scientific rationalism (and no valid spiritual disposition, I would say; he stigmatizes Martin Luther, who divided Europe in the sixteenth century, as a proto-Hitler).

Thomas Zipp, Installation view, 2013; Courtesy of the artist and Kaufmann Repetto Gallery.

The basement of the gallery appears quite different from the cold and symmetric setting of the ground floor. Here disorder prevails: a video projection, dirty white desks, laboratory uniforms and music equipment occupy the room. These are the props and the video documentation of the artist’s performance at Teatro Arsenale in Milan, The Pentothal Analyses (Un ballet de cour) – a work about drugs, non-rational impulses and sexual urges. Again, the revisionist Thomas Zipp points out the way to follow: that of instinct, excess and craziness – the only forces able to move forward an impotent, lethargic mankind.

(Image on top: Thomas Zipp, Untitled, 2013 , one table, six chairs, one sculpture wood, mirror , variable dimensions; Courtesy of the artist and Kaufmann Repetto Gallery.)