Heraclitus wrote, “Nothing is constant but change,” illustrating succinctly his philosophy of the nature of the universe; with her current exhibit Battle Armor, Karen Heagle illustrates this adage, with paintings that show that old motifs can have new life breathed into them. In the past, Karen Heagle has made reference to heroic figures in her paintings: the Incredible Hulk and Xena the Warrior Princess, for example; in her recent show of paintings on paper at Churner and Churner in New York, she revisits some of the same themes and the sense of the heroic, through her choice of subject matter, primarily medieval armor, and combines it with a painterly style that draws from great nature morte and vanitas artists like Hals, Chardin, and Soutine.

When asked how she would describe her recent work and its progression, Heagle replied, “I am developing imagery that reflects autobiographical symbolism … For several years I worked with oil paint on wood panels, but six years ago I began working exclusively on paper. I've started using collage, gold leaf, and copper leaf, preferring to work on a larger scale. I engage my mediums with a blunt yet expressive physicality.” Heagle treats paper as if it were canvas; her figures and objects rendered life-sized and the application of the various leafing sheets give the work an otherworldly light, such that they call to mind Russian icons or the Northern European devotional triptychs of van Eyck.

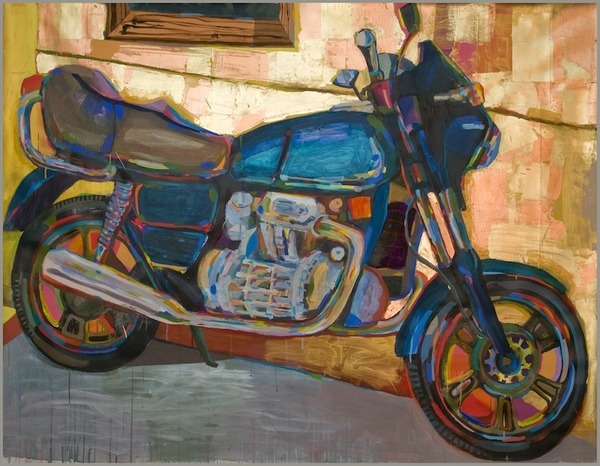

Karen Heagle, Prodigal Daughter, 2013,

acrylic, ink, and collage on paper, 62 3/4 x 79 inches; Courtesy of the artist and Churner and Churner.

It is clear from the start of the show, with Prodigal Daughter (2013), that Heagle is not just mimicking past masters, but is carving out her own niche in painting. Prodigal Daughter depicts a rapid, muscular sketch of a motorcycle leaning against a golden wall of paint and leaf. It announces, slyly, that we are on her trip through this show, the empty seat of the bike beckoning us to come along. Prodigal Daughter serves as a strange cypher when placed in the context of the antique images that comprise the rest of the exhibition. When asked about this, Heagle addressed the idea of melding the contemporary with the past:

“It was a painting that was in my graduate thesis show at Pratt in the fall of 1994. In my current exhibition, this version of Prodigal Daughter is revisiting the themes and ideas it addressed. In essence, it's a type of self-portrait. When I made the original, I was just coming out as gay. So I wanted to make the painting again, almost twenty years later. I wanted to look at how far gay culture has come, related to how far I had come as a gay person. With the increased acceptance of queer culture, I was seeking to explore what queer imagery is in our contemporary culture.”

When viewed from Heagle's perspective, we might see the armor also as a self-portrait. Coming out in the early nineties, the era of Bush I and Jesse Helms, must have taken on aspects of a battle for acknowledgement and equality in society—the same things, one might also add, that painters generally strive for.

Karen Heagle, Battle Armor with Codpiece, 2012

acrylic, ink, and collage on paper 55 x 41 inches; Courtesy of the artist and Churner and Churner.

The real heart of this exhibit, though, is the still lifes of armor that Heagle has culled mostly from the large collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Depiction of armor, knights, and the like has held its place in the history of painting. Rembrandt and Hals jump to mind immediately, as well as tapestry cycles, such as the Unicorn Tapestries. The small helmet said to be worn by Joan of Arc, which is in the collection of the Met, as well as other examples of women’s armor, seem to inspire the story Heagle tells in these works. In Battle Armor with Codpiece (2012), she faithfully renders the suit of metal, with its spiky shoulder plates and other accoutrements. She pays special attention to the shiny metal codpiece, which she admits to enhancing a bit, turning the hard-on into another lance, of sorts, perhaps slyly mocking the sense of narcissistic, peacock-like vanity that the suits lend themselves to so easily. One imagines a further line of study where she might morph the animal with the human, perhaps painting suits of armor designed for horses—metal that both protects the animals and, more often, drowns them at river crossings. As a sidenote, Heagle presents two small portraits of actors, Untitled (Isabella Rossellini) (2013) and Untitled (Charlotte Rampling) (2013)—two stern headshots. On the subject of these images, Heagle turns taciturn but seems to imply that the two actors have both inhabited quite strong roles through their careers, like a protective shell or armor; the actors' facial expressions seem to present a public persona rather than an intimate, internal view of the subject.

Vanity, masculinity, and violence are tied together in a single painting of the beautifully colored bird with a horrific call in Heagle's Peacock (2013). As with suits of armor, the brightly colored plume of the peacock both attracts and repels—it is, of course, this duality, inherent in all of Heagle’s work, that is so compelling; the beauty of her work is that she makes all these contradictions fit together so easily.

(Image on top: Karen Heagle, Peacock, 2013 , acrylic, ink, and collage on paper , 43 1/2 x 52 inches; Courtesy of the artist and Churner and Churner.)