“The blues self is an improvised self. It doesn’t shy away from the difficulty that that entails. When you improvise yourself in culture, you may get some blowback.”[1]

Halfway through the exhibition, a nondescript listening station for John “Jaki” Byard’s 1960 release Blues for Smoke hangs on the wall facing Glenn Ligon’s oil and acrylic text-based reflections and Zoe Leonard’s vintage blue suitcases. When you wander through the exhibition, don’t forget to look for it—you might miss it. If you pause, do take a listen; everything you’ve seen might suddenly become more clear. Jaki Byard was known for his eclectic style as a pianist and composer, incorporating various jazz styles including ragtime, swing, and avant garde into his work, but always maintaining a connection to the blues.

But what is the blues?

Is it a feeling?

An attitude?

Or, as the old saying goes, the stuff that happens between Saturday night and Sunday morning?

“Blues for Smoke” divulges no easy answers. This multidisciplinary exhibition features a broad range of artists such as David Hammons, Martin Kippenbenger, Mark Morrisroe, William Pope.L, Lorna Simpson, Wu Tsang, and Carrie Mae Weems among others. While many works called to mind Fats Waller’s bouncing stride piano, Art Tatum’s virtuosic arpeggios, Duke Ellington’s suave swing, or a turn of the century New Orleans gutbucket blues band, “Blues for Smoke” asks that viewers be open to a wider interpretation of a blues aesthetic, which can be an exhausting exercise when some pieces seem directly connected to the culture of the blues, but many others do not.

Roy DeCarava’s black-and-white portraits beautifully highlight the public-private paradox of social life. Lady Day and Coltrane’s sultry New York is captured in candid images, while stately row houses, stoops, and children skipping rope on the sidewalks remind us of the quotidian side of Harlem on 117th Street (1951). Romare Bearden’s paint on magazine and newspaper collages delight the senses as allegories for the Great Migration, juxtaposing urban and rural life and the movement of culture from Africa to America and back again. In Jeff Donaldson’s psychedelic color whirl Jampact/JelliTite (for Jamila) (1988), three musicians emerge from the geometric patterns in the background. Rendered in AfriCOBRA’s signature “kook-aid” color palette, the work seems to allude to the group’s belief in a collective working process that spurs each other on like members of a jazz combo trading fours and eights.

The works in the exhibition that demand a suspension of disbelief require that we question what we know, or what we think we know. Melvin Edwards’s welded steel sculptures from the “Lynch Fragments” series might prompt viewers to reconsider how painful memories are remembered collectively. The chain links and torqued bolts of Write When You Can and Fire Blossom (both 1991) hint at trauma, bondage, and the Middle Passage despite their abstracted composition. Dusky pinks and muted browns and grays dominate the canvas in the Jack Whitten painting Black Table Setting (Homage to Duke Ellington) (1974). Whitten, who was greatly influenced by jazz, pulled “developers” like squeegees, rakes, and Afro combs across layers of acrylic paint to visualize the effect of being enveloped by sheets of sound. Ever the subversive, Renee Green created the installation Import/Export Funk Office (1992-93) that critiques the process of constructing knowledge. This library cataloguing hip-hop culture is filled with videos and texts culled from the perspective of a white European outsider trying to define a cultural aesthetic by looking in.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Kerry James Marshall (b. 1955), Souvenir IV, 1998, Synthetic polymer and glitter on paper on canvas with grommets, 107 1/2 × 157 1/2 in. (273.1 × 400.1 cm); Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee 98.56.

It might seem odd to spend forty minutes in one place at an art exhibition, but the awkwardness you feel standing at the Blues for Smoke listening station is well worth it. Jaki Byard’s agile, fun, and witty compositions do not apologize for or try to guide us through the dualities and sonic blends we hear. Instead, he seemed to expect that listeners would recognize the fragments of stride, augmented and diminished chords, those be-bop changes, and yes—the blues—when we heard it. “Blues for Smoke” represents a journey through ambiguity and duality, one that tries to convey that a blues aesthetic is more than what can be found in a standard musical progression. The mix of works that alternately refuse and accept clichéd notions of identity sometimes muddle this broader message, and create an unnecessary longing for resolution when resolve should not be needed or expected.

[1] Bennet Simpson (exhibition curator) quoted in “Review: MOCA’s ‘Blues for Smoke’ captivates and improvises” by Christopher Knight http://articles.latimes.com/2012/oct/29/entertainment/la-et-cm-knight-blues-art-review-20121029

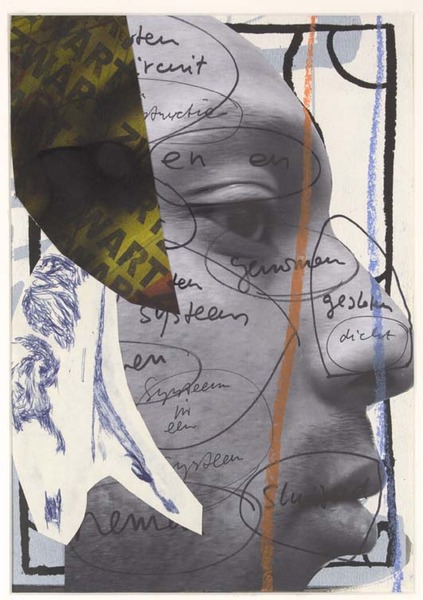

(Image on top: Romare Bearden (1911–1988), Pittsburgh Memory, 1964, Collage of printed papers with graphite on cardboard, 8 1/2 × 11 3/4 in.; Collection of halley k harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York. Art © Romare Bearden Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.)