The obvious needs to be stated before anything else can be said: We are avid consumers of celebrity fanfare and pop culture. It’s an inescapable fact of the cosmopolitan lifestyle. Tabloids give us the dirt, paparazzi provide the candids, while exhibitions and premieres put it all on a pedestal in a glitz-grunge cocktail of truth and fiction. The proportions of each may vary from drink to drink, but be it ambrosia or swill, we can rarely resist celebrity libations. James Franco’s second Peres Projects exhibition GAY TOWN dives straight into the deep end of a very distilled blend of this self-referential pop-culture elixir.

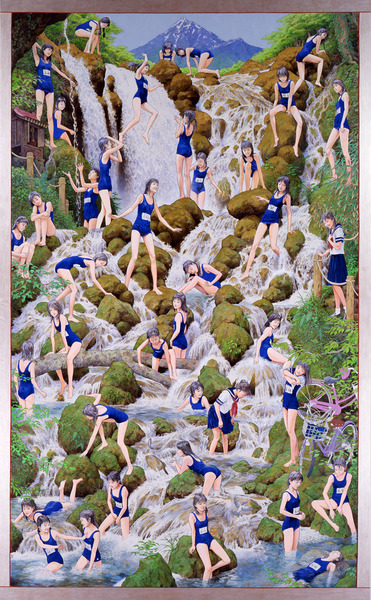

Presented in tandem with the films Oz the Great and Powerful and Interior. LeatherBar. at the 2013 Berlinale, Franco’s newest showing opened on February 9th on the grand boulevard of Karl-Marx-Allee to a temporary gallery space packed shoulder to shoulder with art aficionados and gawking Francophiles. Featuring five hundred works in total, the exhibition boasts paintings, videos, projections, mixed media pieces, and a huge collection of digitally printed throw blankets, which line the entire exhibition space top to bottom. The opening event approached levels of spectacle with the commingling of a frenzied crowd and a wall-to-wall installation that sought to conflate the artist’s personal and public, artistic and filmic constructed personas. Parodies of characters such as Spider-Man and Oz, both played by the Palo Alto native, make cameos in various works throughout the exhibition. The ultimate insider-outsider and self-proclaimed master multi-tasker, Franco’s GAY TOWN seems excessively tongue-in-cheek to an almost overwhelming degree. Coupled with the innumerable, repetitive, and seemingly empty references, viewers are left to navigate largely without a clear roadmap of what they are meant to experience. Cows and cowskulls, perhaps tacitly indicative of a herd, are a recurring theme.

James Franco, Gay Town, Installation View, Peres Projects, Berlin, 2013; Courtesy of the artist and Peres Projects.

Autobiographical in nature, many of Franco’s pieces were created on the go in hotel rooms, movie trailers, and other makeshift studios while working on other projects. Normally icons of private comfort and familiarity, the blankets that take on such a prominent role in GAY TOWN adopt notably different implications when Franco’s self-portraiture is emblazoned upon them, as something cloaking the user.

The elephant in the room, though, is the title of the show itself, which remains unaddressed directly and left unexplained in the official press release. Instead viewers are left to ponder its potential meaning and draw their own conclusions much as they are expected to do with the conglomerate of self-referential blankets and other installation material.

James Franco’s exhibition GAY TOWN runs until March 9th, 2013. On March 1st 2013 Peres Projects will open its new gallery space on Karl-Marx-Allee 82.

(Image on top: James Franco, White Snow , 2012, oil and mixed media on canvas, 100 x 100 cm; Courtesy of the artist & Peres Projects.)

'

'