How we use images and information is changing, therefore, copyright is changing. The image has migrated away from an object of economic value towards one of heightened cultural capital. Social media has developed in such a way that sharing information has become synonymous with sharing images. Infinite copies of images act as citations to shared opinions and data points. Yet the image is not always tied to the fate of a descriptor, it has also been freed from its referent. The image is loose and free to form its own meaning in the slurry of an image-sopped society. As artists, you are at the forefront of this evolution in societal structure. This article examines how a culture of prosumers (producing-consumers) fueled by rapidly evolving technologies of reproduction are changing how we use and reuse images, how this usage is in conflict with the historical development and lawful applications of copyright and finally the alternatives to copyright that have developed to bring our modes of production back in line with our codes of law.

A New Use of Imagery

Once a tightly controlled representational thread of information, images are traded freely and openly, often without regard to the copyright bearer thanks to technological advances in reproduction. Counter-intuitively, this has produced a kind of golden-era in image production over the past half-century and even more so today. Image aggregators such as Tumblr have paved the way for new practices in curation that have ultimately begun to create new aesthetic trends and tensions. One instance of this is the arts tumblr Jogging, a stream of images which has built its own aesthetic sourced from a community of users. Jogging represents a specialization of the practice that has become a normal mode of functioning for many internet denizens. Another force of image alterity comes in the form of machine generated imagery such as new media art, glitch art, 3-d modeling art and the like, something which has come to be termed the New Aesthetic. This alteration in the production and reception of imagery of course leads to concerns over value, both economically and substantively.

![]()

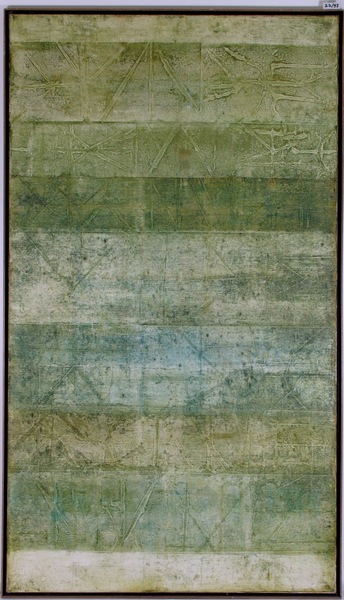

Adam Ferriss, Caelulum, 2013; Courtesy of the artist.

Bruce Sterling in his essay on the New Aesthetic (linked above) says of machine generated imagery, “Valorizing machine-generated imagery is like valorizing the unconscious mind. Like Surrealist imagery, it is cool, weird, provocative, suggestive, otherworldly, but it is also impoverished.” There is a fear of loss, naturally, yet I remain optimistic that this “impoverishment” is merely a reaction to the change in the status of the image, a change which will be dealt with and recodified through common agreements such as copyright (or hopefully something else more in tune with contemporary practices). While it may be true to say that images which have been removed from their original context and realigned with a new set of meanings dependent on the context within which they are shared have lost something, let’s remind ourselves that these images are still very reliant on the affect of the viewer in activating their meaningful potential. We don’t live in a world of meaningless images; we do, however, live in a world where the meaning of images is free to shift and realign as they traverse context after context online. It’s a good thing.

Lessig’s Refrain

Lawrence Lessig is a Harvard Law professor and founder of the copyright alternative Creative Commons. At the beginning of one lecture he gave on the history of copyright in 2002, he started with developing an operational refrain for contemporary production: “Creativity and innovation builds on the past. The past always tries to control the creativity that builds upon it. Free societies enable the future by limiting this power of the past and ours is less and less a free society.” Image-makers/takers and archivists must be aware of their position in the imagistic society in order to fully appreciate their rights and obligations. First, let us take a quick look at the history of copyright to see how it has been used and how it is currently used before we look at alternatives.

A Short History of Copyright (uncited)

Copyright was first codified in 1557 as a state-sanctioned monopoly of printing rights. At the time, Queen Mary, a Catholic in a newly Protestant land, ascended the throne and implemented copyright as a way to prevent the publication and dissemination of Protestant literature. Following her short reign, Queen Elizabeth retained the copyright decree but switched the object of repression to Catholics instead of Protestants. So began a centralized form of censorship and control with a few loopholes to maintain creative production such as fair use. Copyright tends to remain on the side of large organizations and companies even today. Companies such as Disney ruthlessly defend their copyrights even though many of their characters were appropriated from fairy tales in the public domain. Disney has gone so far as to push to extend copyright protections as they currently exist in order to prevent their material from entering the public domain. Mass technologies of reproduction (the Internet) have complicated the centralized control of information (images included) and increasingly made the notion of copyright a vestigial notion with legislation scrambling to keep up.

![]()

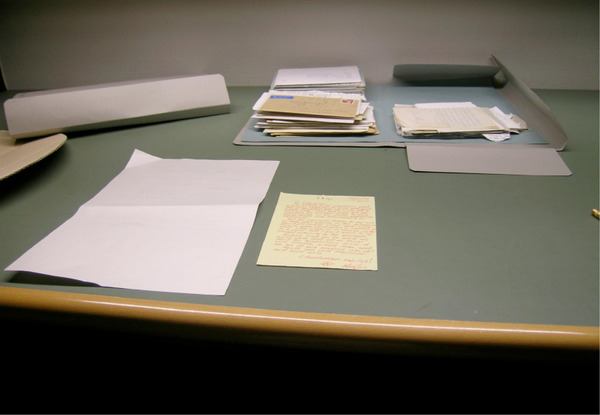

Left, a Rastafarian from Patrick Cariou's, Yes Rasta. Right, an appropriation from Richard Prince's Canal Zone series.

The most recent case in the art world that has brought copyright to the center of attention is the infamous Cariou vs. Prince case. Richard Prince, a prolific appropriation artist who has been working in methods of appropriation such as rephotography since the mid-70’s was sued by photographer Patrick Cariou over his use of images taken from Cariou’s book Yes Rasta. Prince altered twenty-eight images from Cariou’s book for his body of work entitled, Canal Zone. Canal Zonebrought in over $10 million dollars for Gagosian Gallery, 60% of which went to Prince. Ultimately, the courts decided in favor of Cariou, rejecting Prince’s fair use defense. The reasoning behind this ruling many attributed to the manner in which Prince defended his use. This view is typified in an article in the Fordham University School of Law Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Journal by law student Joshua Steinberger: “Richard Prince said this in an interview: ‘I had limited technical skills regarding the camera. Actually, I had no skills. I played the camera. I used a cheap commercial lab to blow up the pictures. . . I never went into a darkroom.’ What is a judge to do with a statement like this?” This is a perfect example of the divide between the codification of image sharing and the art world. While many artists will see this statement as a valid description of a conceptual practice, the code of copyright maintains that technical skill, a craft, must be inherent in original work, paradoxically eliminating considerations of intellectual originality. This is the crux of the issue. As the object becomes more fluid, more vaporous, it is more and more important to take into account the conceptual nature of use as the prime source of creative production rather than the object.

Alternatives to Codified Ownership

Copyright must change to maintain relevance and perhaps it’s more productive to think of copyright alternatives than to try to work within the system of copyright and fair use. Thankfully, alternatives are being developed and are coming into vogue amongst creative professionals and artists. Foremost among these is Creative Commons, a form of copyright that primacies attribution and share-alike freedoms as opposed to use restrictions. Used often in image and moving-image communities such as Flickr and Vimeo, Creative Commons accounts for contemporary modes of cultural production while maintaining freedom for the producer and the consumer to determine the future of the cultural artifact. CC licenses can still allow for non-commercial or commercial applications. Creative Commons comes out of the craft tradition of home computer building and coding. In this milieu during the 1970’s, the term copyleft was developed to designate a form of intellectual property protection that encouraged development and enrichment while preventing the monetization of the project at any point in time. Copyleft is still very popular among developers in the GNU and Linux communities and is increasingly becoming a viable alternative to artists whose work lends itself to development (executable art, for example). The final alternative to copyright is public domain. Public domain functions within the existent system and is the state of ownership that intellectual property falls into once copyright has lapsed. Within the public domain, an object is free to be used, remade, or appropriated for monetary gain. Generally, attribution is maintained solely through courtesy but this is not guaranteed.

Cultural freedom occupies a position that relates to both political freedom and individual autonomy, but is synonymous with neither. The root of its importance is that none of us exist outside of culture. As individuals and as political actors, we understand the world we occupy, evaluate it, and act in it from within a set of understandings and frames of meaning and reference that we share with others.

—Yochai Benkler, The Wealth of Networks

The lesson to take from this schizmatic moment we currently occupy is rather simple. Copyright as it currently is stifles creative production to an extent that current cultural conditions cannot stand. The fact that production moves more quickly and actively opposes current codifications is telling of this. As artists, it is important to recognize oneself as an agent of a larger cultural organism, as a member of the body intellect that can and should be self-aware.

—Joel Kuennen

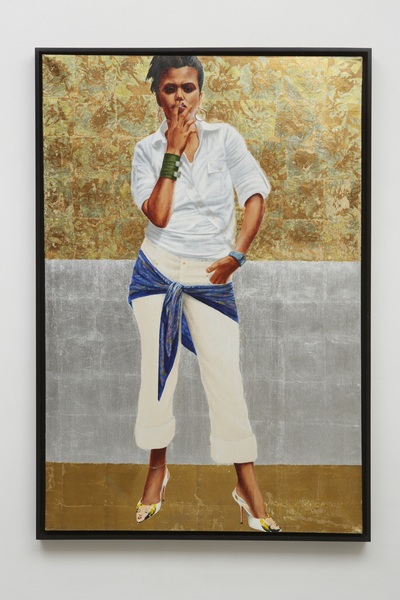

(Image on top: Will Shea, Shawn C. Smith, Mac Bath, 2013; Courtesy the Jogging.)